On the matter of living through it (2022)

Keynote presented on 5 March 2022 at the Place-Making in Cinema Study Circle convened by Robin Vanbesien, Kaaitheater, BE.

I

Perhaps I should start by saying something about the abstract I sent and which functions as an introduction or invitation to my talk, which I’ve entitled “On the matter of living through it.” The abstract reads:

In a rather cranky interview with Mediapart in early January of this year, Jean Luc Godard, in explaining his criticism of the news outlet, said: “A fact is something that happens. But we mustn’t forget that it’s also something that doesn’t happen. And as far as I’m concerned, what doesn’t happen between us today is more of a fact … much more important than what does happen.”This wouldn’t be a terribly profound socio-epistemological point except for the caveat he makes: “Living through it is another matter.” What does it mean to live through what is not exactly happening? What kind of story can one make of it? What kind of scene does it entail? Can you place it or is it always displaced? In this talk, I will address some writing challenges I’m facing as I try to assess the balance of political forces in the crisis-ridden Euro-American capitalist world.

The abstract was a placeholder, by which I mean that it stands in, holds the spot, for what should be there. What should be there in the first instance is a clear sense of the subject of the talk. But, I really didn’t know what I would talk about and was late in sending it to Robin and that’s what I came up with, having recently read the Godard interview. The abstract also stands in for, holds the spot, in the second instance for what will come later. It should be anticipatory for both of us. Robin liked it better than I did, which was good. But for me it didn’t settle at all the matter of the concrete subject of my talk or clarify the details out of which it would be made. It merely reinforced the idea that I was living through something not happening, which was not yet intellectually interesting. And to make matters more complicated for me, the part of the Godard interview that I kept coming back to was not his comments about the facticity of what isn’t happening, but his rather Jesuitical admission that he has five quotations or textual passages that “stay in my memory and which I sometimes repeat in the evening to see if I still remember them.” I had the impression that it was this practice of repetition, of placing these words into the rhythm of his everyday life, as catechism, as infrastructure, that kept him connected not only to his own films but to a practice of thinking required for making them. As he says, “The five phrases, for five fingers, which I have remembered for years, and that I try to repeat to myself, as a “vade mecum” or reference. I do it automatically, and sometimes I try to think of them a little, to stay with them. In general, especially when I’m going to sleep.” Since I usually feel when I’m starting a new writing project that I am always beginning again, anew, as if I’ve no method, style or experience, I found this practice of regularly reciting one’s textual anchors fascinating and potentially helpful.

I won’t bore you with all five of Godard’s quotations. The one I like best is the last line of philosopher Henri Bergson’s book Matter and Memory. Godard says that it was sent to him by a former location manager-- “I had already cited it, he recited it back to me, then I got Alain Badiou to say it in Film Socialisme.” The quotation reads: “Spirit borrows from matter the perceptions on which it feeds, and restores them to matter in the form of movements which it has stamped with its own freedom.”[1] This is a profound statement, bearing many meanings, one of which is that it could function as a definition of a certain kind of cinema, notwithstanding Goddard’s admission that “I never really understood the word ‘perception’.”[2]

II

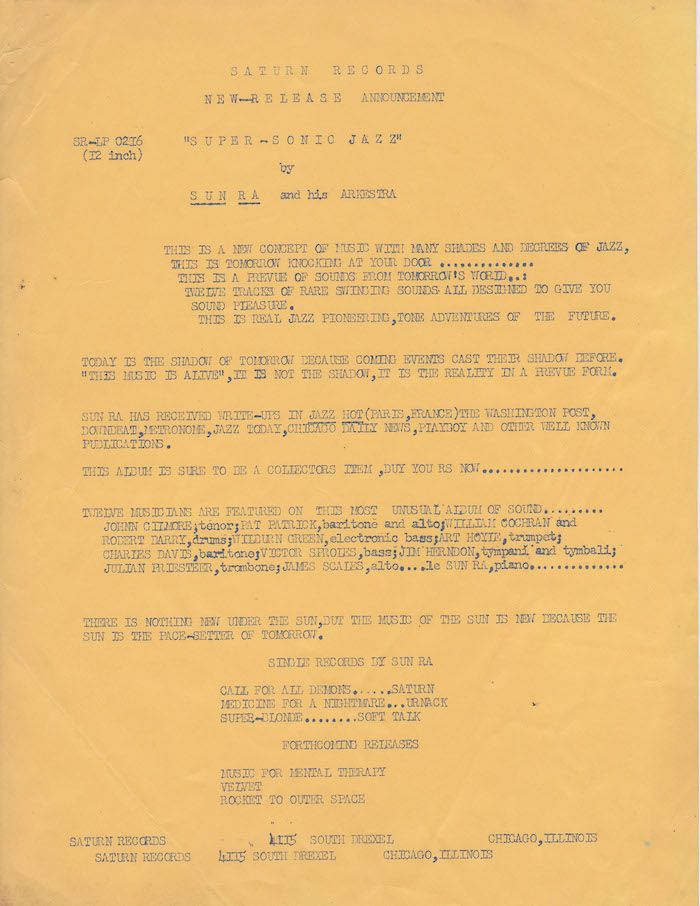

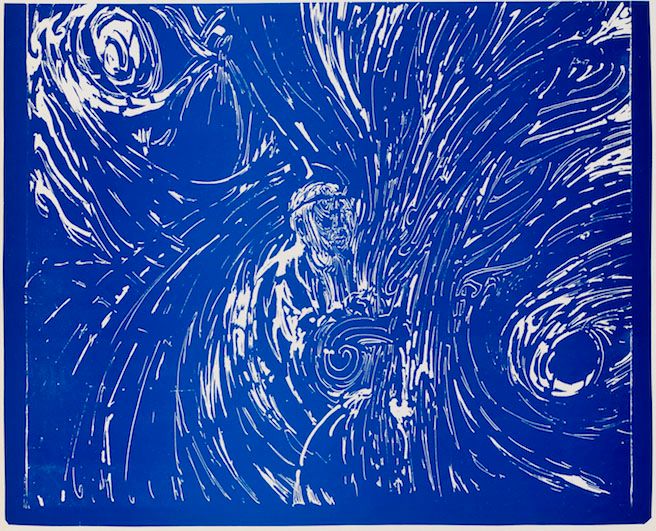

Today is the shadow of tomorrow because coming events cast their shadow before. Sun Ra, A Super-Sonic Jazz Press Release c. 1962, typewritten xeroxed paper, 11 x 8 1/2 in. Courtesy David Nolan Gallery with cover art from Sun Ra and his myth science arkestra, “Cosmic Tones for Mental Therapy” (@1970)

Robin has assembled us here to form a study circle to address some questions about filmmaking and radical consciousness, particularly in relation to what he calls place-making. Although I am not a filmmaker or a visual artist, some of these questions resonate with ones that I think about too, including what practices nurture refusal of both the representational and the socio-political-economic terms that order our existence and our knowledge of our existence, our knowledge of what is and isn’t happening in general and to us, whoever the us is we’re referencing.

In my work, I’ve tried -- although not always succeeding -- to find a writing and a thinking practice that would 1) make common cause with the people whose lives are most impacted by the subject of study; 2) conjure that complex meeting of force and meaning that is social life where slavery, colonialism, forced migration, poverty and exploitation, war, occupation, dispossession, imprisonment, and state violence (all the nastiness) dominate; 3) animate lives and knowledges lost or made invisible or repressed or trivialized by those forces of domination; and 4) acknowledge creatively the mode of production of the writing itself. I’ve tried to show either argumentatively or by demonstration how bloodless categories, narrow notions of the visible and the empirical, and institutional knowledge rules of distance and control produce analytic and social separations that do not help us develop a more accurate and sympathetic view of humanity under conditions of dehumanization, to use Michael Taussig’s phrase.

Or help us produce a particularly accurate or helpful view of how people, with all their conscious and unconscious contradictions and complications, inhabit and act out what, for lack of a better word, I will call political consciousness. So much of my writing is about this poorly named socio-political state of being and the mise en scene of its articulation: about the trouble a ghost -- or sometimes it’s just a minor detail or a trace of something previously obscured -- the trouble these bring and the something-to-be-done that emerges, arises when things are not in their assigned places anymore, when people who were meant to be invisible show up noisily demanding without any signs of leaving, when the present seamlessly becoming the future gets jammed, when the present wavers. When the present wavers something will happen that is never given in advance but which has to emerge out of and grapple with the feeling that fate is shifting that something is being freed and the reach for it is everything. Sometimes this is new and raw for people and all the emphasis is on the political, on the space of social movement activism with its very organised vocabulary and rules of engagement, and on the heady feelings of purpose, solidarity and being in struggle together that it can produce and which it also demands.

Sometimes this consciousness seems removed from anything remotely resembling the political as we know it because the situation is too dangerous, because your time is already completely taxed, because there’s no functioning political thing like a state that hasn’t already made its abandonment of you its reason for being, because you’re very well aware of your “quiet encroachments” and that you can mobilize thousands quickly if desired.[3] Sometimes this consciousness is deliberately not a concerned or outraged political consciousness rooted in a belief (explicit or implicit) in the determining power of the ruling economic and geopolitical systems but rather is a consciousness rooted in what Cedric Robinson called a “comprehension” of the different terms on which you are living and dying and doing much in between including finding your degrees of freedom.[4] This consciousness is rooted in the ability to “conserve,” as Robinson puts it, a “native consciousness of the world from alien intrusion, the ability to imaginatively re-create a precedent metaphysic while being subjected to enslavement, racial domination, and repression.”[5] I’ve called this ability being in-difference, a mode of being or becoming unavailable for servitude or subordination or for living under conditions you had no part in making and which are designed to make you into nothing or into somebody only useful for them.[6] This ability brings you to the utopian margins, sometimes in a state of fugitivity on the run from the law anxious and furtive, sometimes agitated in the thick of struggle insurrection and slogans at the ready, sometimes already almost completely elsewhere quietly farming or baking bread for the neighbourhood on Fridays without need any longer for naming this as anything other than farming or baking bread, sometimes with the belief that aliens from other planets are exactly what’s required to protect you from “alien intrusion.”

This partially explains why, notwithstanding the album or film title, Sun Ra didn’t exactly argue that space was the place, but rather that he was from outer space, Saturn to be precise. His Black metaphysics also follows the Bergson formula--spirit borrows from matter the perceptions on which it feeds, and restores them to matter in the form of movements which it has stamped with its own freedom--which actually sounds a lot like Robinson’s description of the “raw material of the Black radical tradition,” whose epistemology, he wrote, “granted supremacy to metaphysics not the material."[7] (Although not in the way you might think.) In 1945 as Herman Poole Blount and after a stint in jail for refusing military conscription, Sun Ra made the trip, part of the second great migration north, from Birmingham Alabama to Chicago, the place the sociologists St. Clair Drake and Horace R. Cayton called “Black Metropolis.”[8] By 1952, Sun Ra was certain that what existed couldn’t possibly be true, as Ernst Bloch put it. “There is no place in the universe where death is deified except on the planet earth,” Sun Ra and and his esoteric research group, Thmei Research argued. As Matthew Harris writes: “To accept one’s place in the given meant belonging to a burial society. Those were the worldly terms of existence. [Sun Ra] being a citizen of Saturn didn’t live on those terms. Sun Ra was not born; he arrived,” as he liked to say. And so El Saturn and the Arkestra played atonal music from outer space, having, they claimed, “obtained” “remarkable” results from their experiments on “dope addicts, drunks, angry people, mental patients, the depressed and …[the stubborn].”[9] Of course, outer space music, dancing, and serious study found a place in various venues on the south side of Chicago, including in Mary Abraham’s home filled as it was with the books her son Alton and his friend Sun Ra collected, but, to quote Harris again, “what took place was a collective process of staging an exit,” all aliens welcome, one might add.[10] Spirit borrows from matter the perceptions on which it feeds, and restores them to matter in the form of movements which it has stamped with its own freedom.

III

Tents Nirim 1949

For a long time now, I’ve been dealing with ghosts, traces and seemingly minor details from the past and the present, the problems with representational repair work, the limits of documents and the documentary form, the absences in and that structure the archives of the powerful and the ordinary, the condescension or “severity of history,” and with the rather elaborate scripts of what is not happening, or so it seems, even in the best progressive and most self identified radical circles.[11] And yet, this knowledge and experience doesn’t quite provide a ready formula; each situation, it seems, requiring to some extent its own form, one that registers or at least gestures towards the determining conditions or what Robin calls the “wider causalities” as well as towards the modes of living through it in place or living through it to another place.And so, I am always interested in how other writers find the form or the formula. Because I am supposed to be writing a small book and I know a little about its subject from my political and radio work, I was especially keen to read Adania Shibli’s Minor Detail, a book of 100 pages in English translation, published first in Arabic in 2017 and then in English in 2020, which my friend Basak gave me for my birthday this year, with the implicit but very mild admonition that I should have already read it.[12]

The book is divided into two parts, equal in length. The first part is set in August 1949 at the Nirim military outpost in the western Naqab or Negev desert, close to the border with Egypt. “Nothing moved except the mirage. Vast stretches of barren hills rose in layers up to the sky, trembling silently” are the book’s first scene-setting lines. A platoon of soldiers led by a fastidious commander (known as he) arrives at the ruins —“two standing huts and the remains of a wall in a partially destroyed third”—of the old Kibbutz destroyed by the Egyptian army the year before with a mission to secure and clear this part of the desert by searching for and killing all the Palestinian Bedouins they find. After two days or so, the patrol encounter four people in the hills, three men and a girl perhaps around 15 years of age, a dog, and six camels. They shoot and kill the men and the camels, leaving them without burial, and take the girl captive. It’s not clear whether they also took the dog or whether the dog followed on its own. Stripped, forcibly washed and doused in petrol, the girl is raped by twenty soldiers and the commander, at the commander’s invitation, before being driven 500 meters from the camp, shot, and buried where she fell. The narration is affectless, clinical almost, at once mimicking the obsessive washing routines and distant authoritarianism of the commander and at the same time punishing him. On his first night, the commander is bit by a scorpion and his terrible pain, oozing infection, paranoia, and delirium are treated to the same narrative coldness. The only sound of life, the only movement with spirit, in this section are the girl’s shouts and the constant barking and wailing of the dog, who, in the final scene of part one, the commander tries, in vain, to muzzle with his bare hands.

The second part is set in the book’s present first in Ramallah and then in a woman researcher’s car as she makes a trip. If, as a figure or character, the commander is all disassociative exteriority, a sum of commands and actions at once rational and septic, the woman (known only as I) is all neurotic anxious interiority. Narration moves from a very distant third person to a very close first. In part two, more things happen in the same number of pages because living through it requires more thought and effort.

Part two begins with a woman lying down to rest after a day of cleaning her new house, having moved into it a few days earlier for a new job she’s just started. As soon as she lays down to sleep, “a dog on the opposite hill began to howl incessantly” and she can’t sleep. The woman sits every morning at a table by the front window and drinks coffee before she goes to work, “implying” to passersby that she “lived a peaceful life.” She doesn’t. She doesn’t “navigate” the “borders imposed between things” well, too often “trespassing” and doing dangerous things like asking soldiers to put away their guns when they demand to see her identity card on the minibus, leading her to stay alone inside the house as much as possible. She cannot stand dust or dirt and admits that she is “unable to evaluate situations rationally.”

She’s sitting at her front table one morning and reading the newspaper article that exposed “the incident” described in part one. What draws her to the story, “what made it begin haunting me,” was “the presence of a detail that is really quite minor when compared to the incident’s major details” (62): that is, the date it occurred. While “there was nothing really unusual about the main details especially when compared with what happens daily in a place dominated by the roar of occupation and ceaseless killing,” (64) the fact that it happened on a morning twenty-five years exactly before she was born, will, she says, “never stop chasing me.” (65) The dog keeps barking and the woman decides to investigate the “rape and the murder as the girl experienced it,” a subject on which the newspaper article is completely silent. The woman is ambivalent about the whole thing: she thinks the investigation is “completely beyond my ability” and that there’s “no point in my feeling responsible for her, feeling like she’s a nobody and will forever remain a nobody whose voice nobody will hear” because there’s “enough misery in the world” and “there’s no reason to go searching for more and digging into the past.” (69) But the dog keeps howling and she sets off in a car rented for her by a colleague since she doesn’t have a credit card and with an ID borrowed from a friend since she doesn’t have one that permits her to travel to Area C and beyond where both the archives and the site of the incident are. Juggling multiple maps, her own fears, the increasing “absence of anything Palestinian” (79), and the complicated system of enclosures (walls, checkpoints, segregated road systems) that structure movement for Palestinians, she arrives, after an encounter with a young girl aggressively selling chewing gum at the Qalandiya checkpoint, at the Israeli Defense Forces History Museum in Tel Aviv near the old railroad, where she finds “no valuable information… not even small details that could help me retell the girl’s story” (85), which, to be honest, is not surprising. Had our researcher been thinking straight she would have known that the girl’s voice and feelings were never to be found there or at any of the other IDF museums dedicated to the military and paramilitary forces of settlement.[13] She gets back in the car with her pre-1948 and post-1967 maps, hungry, anxious, exhausted. She gets to Nirim, gives an Israeli man in his 70’s a false name and purpose and he tells her some history and shows her a photograph of something she’s read about in the newspaper article.[14] She realises this is not the scene of the crime, takes the booklet the man gives her and keeps going, not finding any details “major nor minor.” (96) She feels lonely and helpless by turns panicked and calm. She spends the night in a guesthouse where she smells petrol and tries to wash the smell off extravagantly and pleasurably using all the full-flowing hot water she normally doesn’t have, and where again she hears a dog barking. Woken by the sound of bombing in Gaza or Rafah-- she’s not sure--she heads for the site where the girl was killed, meeting up with another dog or perhaps the same one, as well as a silent older Palestinian woman who the researcher later regrets not asking whether she knew anything about the girl whose death haunts her. She gets out the car in a signed military zone and shooting range. She notices a group of camels and a group of soldiers. The soldiers shout at her, ordering her to stop moving. They raise their guns. She thinks she needs to calm down and reaches for the packet of gum in her pocket. “And suddenly, something like a sharp flame pierces my hand, then my chest, followed by the distant sound of gunshots” (119).

Adania Shibli’s Minor Detail is, as Pankaj Mishra wrote, a powerful “blend of moral intelligence, political passion, and formal virtuosity.” It is a very smart and moving book and the writing is enormously disciplined. Shibli is able to do as Calvino advised in Six Memos for the Next Millennium: to remove the weight from the people, from the completely overwrought situation, and from the structure of story and language, so that this story can be broached by the researcher and held and retold by Shibli. The two parts and the two main actors enact what’s between them--walls, checkpoints, barbed wire, expulsion, dispossession, atrocity, the genocidal basis of the Israeli settler colonial project--so that the “wider causalities” appear distinctive to the experience of them: at a distanced remove, shrouded in ideology, command and control, and pathological denial in part one and completely imbricated in the minute fabric of everyday life in the second part. The Israeli commander repeats his routines and orders without respite while burning up with poison and delirium. The Palestinian woman has to think ten steps ahead, juggle old maps and ones being continuously recreated without her knowledge or approval, get help from a lot of people both trustworthy and not, depend on luck or fate, and risk her life just to leave her house and drive to the archive in the next town. The fictional details Shibli adds to the historical facts of the real event that part one dramatizes — the spider bite and the barking dog—are very carefully selected, powerful, and deeply animistic. The reader must tread carefully around them. The convergence of past and present in the disturbing ending is both reckless — the researcher knows that she has to navigate this border carefully—and inevitable. The inevitable outcome of the counterinsurgency logic of Israeli statecraft and the inevitable outcome of Shibli refusing a certain sentimentality on behalf of her character: “It’s an innate tendency, one might say, towards a belief in the uniqueness of the self, towards regarding the life one leads so highly that one cannot but love life and everything about it. But … I do not love my life in particular, nor life in general, and at present any efforts on my part are solely channelled towards staying alive” (63). At which she fails, in the end; an ending that puts into question the relationship between major and minor details, the singularity of the Bedouin girl’s ghost, and the terms involved in making common cause as writers with those about whom or with whom we are writing.

I would like to say a word on this last point. In Minor Detail, everything begins and to some extent ends with the soldiers, their routines, their mission, their place in the making of the Nakba/catastrophe that is the basis for the state of Israel’s founding and continuation as an apartheid state and occupying force. The girl is nothing to them, not even a nobody, more a nothing. The idea of any common cause with her is precisely what the soldiers are there to prevent from ever happening then and now. This is one point the book makes brutally and without mercy and it works, I think, because the story is told without recourse to the traditional conventions of representational repair. For one thing, we barely see the violence done to the girl in 1949. The violence is present, as bare factual, rendered in that cold distanced language Shibli uses in the first part, but it is emphatically not spectacularised. The violence occurs as denouement and also as part of the platoon’s monotonous repetitive routine, the desert already a scene of haunting. There’s neither embellishment nor speculation, and in fact Shibli says less than what she could: the actual newspaper article contains more of what the soldiers did, said and later remembered than appears in her fictional rendering. Moreover, this one incident was part of a full-scale military operation to ethnically cleanse Palestinian Bedouins from the desert in order to seize land that continues today, under the guise of afforestation and under cover of tear gas drones.[15]

Shibli is a gifted writer, perfectly capable of imagining the girl’s experience and feelings, yet we are told only enough and no more. There’s a sparseness in the deliberate and controlled language that prevents any voyeurism and that also insists that the girl’s experience cannot be found there in that place, among those words, in that scene. But the researcher wants the story as the girl experienced it, that’s what drives part two. At some level the researcher knows that this desire of hers to find the girl’s name, her kin, her voice, her feelings will cause trouble. (As the reader is reminded many times, she can’t evaluate situations rationally and never knows what should be done without calamitous consequences.) The girl’s experience is a border or a blindfield that needs to be respected, Shibli shows, not because it’s irretrievably lost or unknowable but because the researcher is still in the story. Being still in the story, it is dangerous. As in part one, the story begins and ends with the military occupation. As in part one, the woman is a nothing to the soldiers or to the state, common cause is what they are organised and tasked to prevent. As in part one, the violence at the end of the book occurs as denouement and also as a routine shooting that inaugurates another “minor detail” to be covered up in official records. In her novel Beloved, Toni Morrison described what she called “rememories” as those collectively animated worldly memories that are always waiting for you, regardless of whether they happened to you or not. Morrison writes: “Where I was before I came here, that place is real. It’s never going away. Even if the whole farm--every tree and grass blade of it dies. The picture is still there and what’s more, if you go there -- you who never was there-- if you go there and stand in the place where it was, it will all happen again; it will be there for you, waiting for you.”[16] This warning is made literal in Minor Detail and we should heed it. Sometimes we are not actually in the same story or not in the same story anymore and it is easier to find or imagine the experience of the lost girls without getting disappeared ourselves, but the question of the relationship to the present and those wider causalities remains operative still.

IV

Algerian riflemen

I’m supposed to be writing a short book for Seagull Press entitled Scenes of Flight. There is a 3000-word proposal that begins with a discussion of the complex trajectories of movement across Africa, West Asia or the Greater Middle East and Europe, and within Israel Palestine for people who are forced to cross borders illegally and what it means to see this movement as part of the radical traditions, always criminalised, of resistance through escape and flight. It poses the question of whether the thousands of fugitives on the move today, in varying degrees of militancy and political planning, have entered upon a general strike against the conditions of work and life in which we are all entwined and whether such a strike might signal, as W.E.B. Du Bois argued was true in an earlier era for the millions of African American slaves who walked off the plantations, a breach in a system that presumes its immortality?[17] It concludes as follows:

“Capitalism lurches from crisis to crisis more and more frequently and is incapable of resolving them without ever increasing financial and military assistance from the state, even as its anti-state ideology sounds louder and louder. The ongoing redistribution of resources from public entities to private ones in this context of enhanced militarism and securitization has led to more widespread social abandonment and more entrenched inequalities within and between countries. The major capitalist powers in the West seem either not to understand or to be in denial about the decline of western hegemony and the quiet but definitive shifting of the world system east, a shift with profound consequences for those of us living in the West. The capitalist democratic state is also weakened, in the case of the US and the UK internally conflicted to the point of incapacity, creating both resurgent authoritarianisms and a legitimation crisis serious enough to threaten the state form itself. There is widespread political opposition at various scales which, while disorganized, nonetheless encourages both the normalization of routine counterinsurgency policing and a growing sense that, shut out of participation in the existing economic and governing systems and facing ecological catastrophe, people must find another way to live. As in previous moments in the history of capitalism, the movement of people is key: captive, forced, free, fugitive, one by one, en masse. And as in previous moments, people organize politically and prepare for a new life in flight.

It is difficult to take the measure of the changes we are living through, to determine what is dominant, residual and emergent in what is always a fragmented disoriented out-of-synch totality. We see and don’t see what is coming, always. In The Sociological Imagination, C. Wright Mills advised to search “among all the details” for the “main drift… of the underlying forms and tendencies of the … society.”[18] Scenes of Flight proposes a small book that presents some scenes from the past, the present, and the future that might evoke the main drift of our present moment with an eye to intervening in its trajectory. The scenes will be anchored by visual images, whether derived from art works or archival items or works of fiction. These images are not so much the main subject of the scene as they set the scene, thus functioning less informationally and more scenographically, almost as if they were film stills. The purpose of presenting scenes is to show rather than merely to tell. This kind of demonstration aims to restore what theory often closes off -- the concrete, the particular, and the contingent--and to animate it with the worldliness that demands it in the first place, a suitable format for working with subjugated knowledge that is often elusive, secretive, and itself a hybrid of facts and fictions.”

Three image details have accompanied this proposal from the beginning. They are Ikko’s writing fragments in Kossi Effoui’s book The Shadow of Things to Come, a coded link to the crocodile maroons and their friends who help our unnamed narrator escape from an unnamed country in Africa after the “time of Annexation,” where his refusal to fight in the war “along routes of future pipelines” against the insurgent border people living in the forest means he will either flee or die.

The second image is the other (not the famous one of the Zhong) Turner painting, “Disaster at Sea,” made in 1835 in response to the wreck of the transport ship the Amphitrite off the coast of France near Calais in 1833, and the necropolitical decision of the captain that it would be better for 30 members of his crew, including himself, to die than for there to be even the possibility of any escape by the 103 women prisoners and 12 of their children he was transporting to New South Wales (Australia) as indentured servants bound to work the settlement into a colony.

And third is a photograph of Algerian riflemen in Bordeaux in August of 1914, where the men look very fed up already, arms crossed, staring angrily into the camera. But these are not the soldiers I’m looking for. I’m looking for the 10e Compagnie of 8 Battalion of the Régiment Mixte de Tirailleurs Algériens (although I think it was the 4th not the 8th battalion), who after refusing an order to attack during a retreat, were all executed on the 15th of December 1914 near Zillebeeke in Flanders.

Each image conjures obliquely a problem, a scene, a space for thinking about our world and its drift today that matters to me: the nature of and terms of solidarity or fellowship needed to make a more livable life on other terms than the ones we’re living with; the counterinsurgency, criminalisation and confinement logics embedded since its origins in the modern capitalist world system and its nation-state political form; and the possibility that the armies of soldiers and police anywhere everywhere will refuse to uphold the systems that would completely collapse without them. Together these scenes do not cohere well, are both too intimate and too disconnected from each other to form into a short book, which is supposed to mime the long-essay format. I approach and avoid these accompanying scenes as if they were fixed events rather than spaces for working and working on collective problems. I try to solve the problem through reading not writing, which is probably a mistake but it’s easier. I think maybe these are not the right scenes or the right scenes for me to stay with or that there are just too many of them. One must be chosen because I’m going in circles.

V.

Still, Film Socialisme, dir. Jean-Luc Godard 2010.

I’m going in circles and need to conclude now, so I go back to the beginning and the Bergson quotation: Spirit borrows from matter the perceptions on which it feeds, and restores them to matter in the form of movements which it has stamped with its own freedom. I watch the film again to find it, thirty-six minutes thirteen seconds in. It turns out Godard didn’t remember correctly: Badiou doesn’t recite the statement. He’s in the scene, although it’s hard to see him as he’s sitting in the dark at an angle at a desk his head turned to the side. The statement is read off screen by a young woman who stumbles over it, starting and stopping its recitation several times. Of all the statements made in the film, it’s one of the least memorable, deliberately mangled and trivialized. But then again Godard too is going in circles in that 3-part film, or at least, that was my experience of it. The cruise ship sails as a kind of sealed container around the Mediterranean, fantastic colours ablaze on the dance floor, but it feels like a disaster is brewing and no one realises it. The futility of the political demands in part two—“Notre Europe”—is less a bridge between the delirious escapist present and somewhere else than a partially self-referential cul de sac. Godard seems to be looking for the future in Western civilization’s past source material in the third part, but he can’t see it from there, although I see the common notes I’ve stitched unwittingly: Euro-American responsibility for the ongoing occupation of Palestine, the ceaseless presence of war, the intelligence of a dog, the importance of the sound of meaning. So, I’m in good company at the end here, going in circles too perhaps looking in the wrong place for the right stories of living through to a place, not a speculative philosophical fantasmatic end of the world as we know it, but a place we’ll have to live in where the shifts in the geopolitical order augur the real end to a Euro-American centric world and the unsettling question of the future of Euro-America, a question the Russian war on Ukraine raises dramatically now as we meet.

And so here is where the last words must be lodged. Russia’s belligerence must be viewed within the larger context in which it occurs, a context in which the choice between a racist militarist Euro-American unity (NATO) or a revanchist Eurasia must be refused for what they share: expansionist designs to control the world’s economic, political, cultural and human resources. Whether it is best called neoliberal capitalism, or oligarchic capitalism, or socialist market capitalism, this struggle for global hegemony is already a world war being prosecuted on multiple fronts—from the Greater Middle East across the African continent to the South China Sea—and through multiple means, including transhemispheric trade, economic agreements and communications infrastructure linking China, Russia, Turkey and Iran not only to the old Mediterranean world but to the whole African and Latin American continents. It might be wise for us to remember that the very backward West first rose to world dominance by acquiring power over Eurasia, defeating the Ottoman empire, gaining control over the Indian ocean and the Mediterranean, and isolating China through war and extraction. It looks likely to lose it there in the near future. What this will mean is hard to know. For now, we do know that this war is a disaster for ordinary people—bringing greater levels of extraction and exploitation and new overlords—and a vicious counterinsurgency war, a scorched earth policy of eliminating any and all resistance and opposition. And so, it must be opposed on all fronts. There is political and solidarity work to be done now set to the terms for livable future for the world’s majority: demanding immediate ceasefire and a solution that works to change the social and economic policies that brought war in the first place; forcing the European and US governments to provide a safe welcome for refugees from Ukraine, Russia and elsewhere; and escalating the struggle against the criminalisation of anticapitalist, antiracist and antimilitarist movements. [19] Spirit borrows from matter the perceptions on which it feeds, and restores them to matter in the form of movements which it has stamped with its own freedom.

Thank you.

[1] Henri Bergon, “Summary and Conclusion” in Matter and Memory (1896), trans. Nancy Margaret Paul and W. Scott Palmer. London: George Allen and Unwin 1911, pp. 332. It is the last sentence. A Mead Project online: https://brocku.ca/MeadProject/Bergson/Bergson_1911b/Bergson_1911_05.html

[2] Ludovic Lamant et Jade Lindgaard, “Recontre avec Jean-Luc Godard: ‘on ne peut pas parler’” Mediapart, 3 December 2021. The English version is entitled “An encounter -- with a difference -- with French film legend Jean-Luc Godard. https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/culture-idees/031221/rencontre-avec-jean-luc-godard-ne-peut-pas-parler

[3] Asef Bayat, Life as Politics: How Ordinary People Change the Middle East. Amsterdam University Press, 2010.

[4] Cedric J. Robinson, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition (1983). University of North Carolina Press, 2000, p. 72.

[5] Ibid, p. 309.

[6] Avery F. Gordon. The Hawthorn Archive: Letters from the Utopian Margins. Fordham University Press, 2018.

[7] Robinson, Black Marxism, p. 309, 169.

[8] St. Clair Drake and Horace R. Cayton, Black Metropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City (1945). University of Chicago Press, 2015.

[9] Matthew Harris, Black Religion Under the Sign of Saturn. [Doctoral dissertation University of California Santa Barbara Department of Religious Studies 2022],Ch 4.8, p. 3.

[10] Ibid, p. 21.

[11] The phrase severity of history is from Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker, The Many Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners, and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic. Beacon Press, 2000, p, 7.

[12] Adania Shibli, Minor Detail, trans. Elisabeth Jaquette. Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2020. Page numbers in parenthesis.

[13] The Israeli Ministry of Defense manages ten museums, including 4 in Tel Aviv and Jaffa. See https://english.mod.gov.il/About/Legacy/Pages/Museums.aspx

[14] The statement on the ruined wall: Man not the tank will prevail. See Aviv Lavie, Moshe Gorali, “’I saw fit to remove her from the world.’” Haaretz, October 29, 2003. https://www.haaretz.com/1.4746524

[15] See Dr Ramzy Baroud, “From Tantura to Naqab: Israel’s Long Hidden Truths are Finally Revealed.” 10/2/2022 Countercurrents.org https://countercurrents.org/2022/02/from-tantura-to-naqab-israels-long-hidden-truths-are-finally-revealed/

See also Ahmed Abu Artema, “The Naqab is a key piece in Israel’s apartheid puzzle.” The Electronic Intifada, 23 February 2022. https://electronicintifada.net/content/naqab-key-piece-israels-apartheid-puzzle/34876

[16] Cited in Avery Gordon, Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination, 2nd ed. University of Minnesota Press, 2008, pp. 164–5.

[17] W. E. Burghardt Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America. Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1935.

[18] C. Wright Mills, The Sociological Imagination, 40th anniversary edition. Oxford University Press (1959), 2000, p. 223.

[19] 16 Beaver Group wrote: “the current invasion by Russia of Ukraine is a moment of intensification in an ongoing war [a world war being prosecuted on multiple fronts], which inherits the legacies of a cold war and the hot wars which preceded it, always risking to spill into surrounding territories and justifying new forms of weaponry for forced forms of pacification. These wars … [each] have their locality and specificity, but they cannot be read outside the larger forces at play.” The tactical and strategic nodes of that ongoing war are many and Eurasia at the center of it. See also Lefteaast.org’s statement: https://lefteast.org/lefteast-condemns-putins-imperial-war-against-ukraine/. On the larger Eurasian field, see Alfred McCoy, “Eurasia’s Ring of Fire: The Epic Struggle over the Epicenter of U.S. Global Power.” TomDispatch, 16 January 2022., an excerpt from his new book, To Govern the Globe: World Orders and Catastrophic Change. Pepe Escobar has long been writing about all this.